By University of Michigan November 1, 2024

Collected at: https://scitechdaily.com/faster-than-light-how-x-rays-unravel-mysteries-of-black-hole-jets/\

University of Michigan researchers have tapped into two decades of NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory data to unveil fresh insights into the behaviors of cosmic jets emitted by black holes.

Their studies reveal significant differences in how these jets appear in X-ray versus radio waves, highlighting faster-than-light-speed movements and unique knot formations in X-ray observations, which may revolutionize our understanding of galactic phenomena.

A team led by the University of Michigan has analyzed over twenty years of data from NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory, uncovering new layers of complexity in the study of black holes.

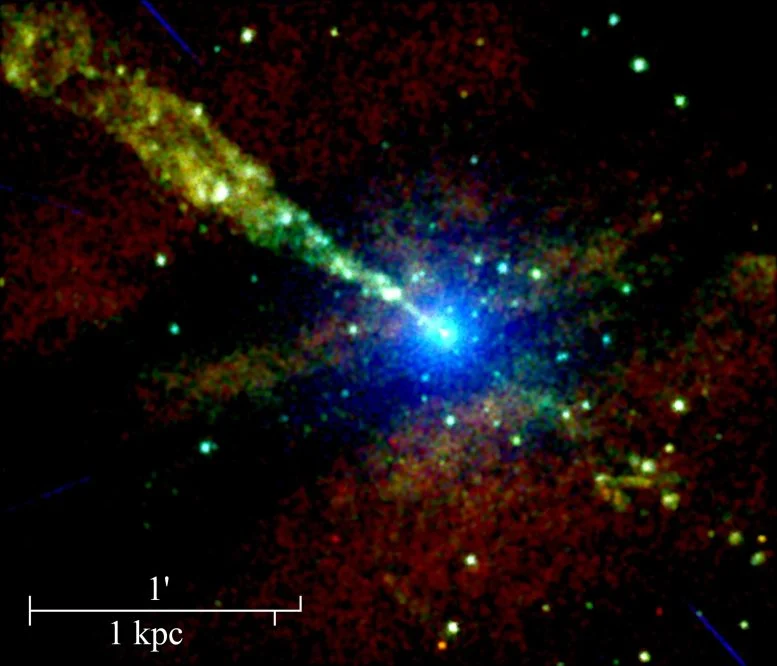

The research focuses on a high-energy jet of particles emitted by the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy Centaurus A. These jets, powerful streams of particles, can be observed through various telescopes, including those detecting radio waves and X-rays. Since Chandra’s launch in 1999, astronomers have been especially intrigued by the unexpectedly bright X-ray signals emanating from such jets.

Initially, X-ray observations seemed to capture features similar to those seen in radio wavelengths, a result that fell short of revealing deeper distinctions. Jets are massive structures, some larger than the galaxies that host them, and they remain a scientific mystery. When jets appear similar across different wavelengths, it limits scientists’ ability to uncover the hidden complexities of these astrophysical phenomena.

New Insights From Chandra Observatory Data

“A key to understanding what’s going on in the jet could be understanding how different wavelength bands trace different parts of the environment,” said lead author David Bogensberger, a postdoctoral fellow at U-M. “Now we have that possibility.”

The new study is the latest entry in a small but growing body of research that’s digging deeper into data to spot subtle, meaningful differences between radio and X-ray observations.

“The jet in X-rays is different from the jet in radio waves,” Bogensberger said. “The X-ray data traces a unique picture that you can’t see in any other wavelength.”

Bogensberger and an international team of colleagues published their findings in The Astrophysical Journal.

Analyzing Knot Movements in Space

In its study, the team looked at Chandra’s observations of Centaurus A from 2000 to 2022. Or, more accurately, Bogensberger developed a computer algorithm to do that. The algorithm tracked bright, lumpy features in the jet, which are called knots. By following knots that moved during the observation period, the team could then measure their speed.

The speed of one knot was particularly remarkable. In fact, it appeared to be moving faster than the speed of light because of how it moves relative to Chandra’s vantage point near Earth. The distance between the knot and Chandra shrinks almost as fast as light can travel.

The team determined the knot’s actual speed was at least 94% the speed of light. A knot in a similar location had previously had its speed measured using radio observations. That result clocked the knot with a significantly slower speed, about 80% of the speed of light.

Implications for Future Research

“What this means is that radio and X-ray jet knots move differently,” Bogensberger said.

And that wasn’t the only thing that stood out from the data.

For example, radio observations of knots suggested the structures closest to the black hole move the fastest. In the new study, however, Bogensberger and his colleagues found the fastest knot in a sort of middle region—not the farthest from the black hole, but not the nearest to it either.

“There’s a lot we still don’t really know about how jets work in the X-ray band. This highlights the need for further research,” Bogensberger said. “We’ve shown a new approach to studying jets and I think there’s a lot of interesting work to be done.”

Continuing the Exploration of Cosmic Jets

For his part, Bogensberger will be using the team’s approach to examine other jets. The jet in Centaurus A is special because it’s the closest jet we know of at about 12 million light years away.

This relative proximity made it a good first option for testing and validating the team’s methodology. Features like knots become more challenging to resolve in jets that are farther away.

“But there are other galaxies where this analysis can be done,” Bogensberger said. “And that’s what I plan to do next.”

Reference: “Superluminal Proper Motion in the X-Ray Jet of Centaurus A” by David Bogensberger, Jon M Miller, Richard Mushotzky, W. N. Brandt, Elias Kammoun, Abderahmen Zoghbi and Ehud Behar, 18 October 2024, The Astrophysical Journal.

DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ad73a1

Leave a Reply