By Amit Malewar 10 Dec, 2024

Collected at: https://www.techexplorist.com/smallest-asteroids-ever-detected-in-the-main-belt/94332/

The asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs was about 10 kilometers wide, a rare event occurring once every 100-500 million years. Smaller asteroids, roughly the size of a bus, hit Earth more often, around every few years.

These decameter asteroids, which can come from the asteroid belt, may cause regional destruction, as seen in Tunguska (1908) and Chelyabinsk (2013). Observing these asteroids could reveal insights into meteorite origins.

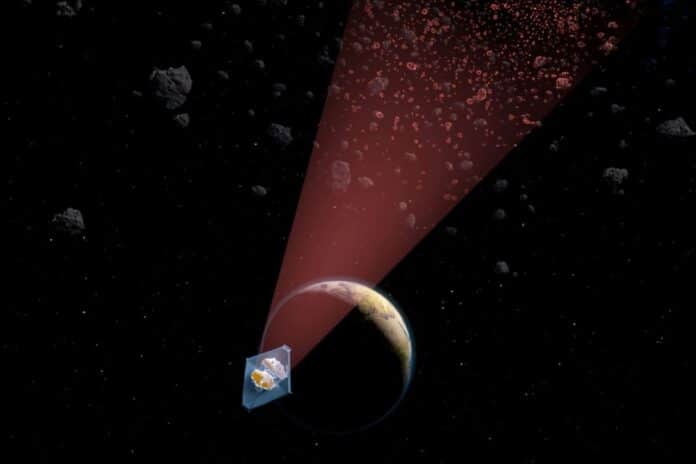

MIT astronomers have developed a new method to detect small decameter asteroids, as small as 10 meters in diameter, within the main asteroid belt, a region between Mars and Jupiter. Previously, scientists could only identify asteroids that were about a kilometer wide.

Using this new approach, the team has discovered over 100 new decameter asteroids, ranging in size from bus-sized to several stadiums-wide. This breakthrough, detailed in Nature, could help track asteroids that may pose a risk to Earth.

The study’s lead author, Artem Burdanov, a research scientist in MIT’s Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, said, “We have been able to detect near-Earth objects down to 10 meters in size when they are close to Earth. We now have a way of spotting these small asteroids when they are much farther away, so we can do more precise orbital tracking, which is key for planetary defense.”

MIT professors of planetary science Julien de Wit and his team, primarily focused on studying exoplanets, were part of the group that discovered a planetary system around TRAPPIST-1 in 2016. Using the TRAPPIST telescope in Chile, they confirmed that the star, located about 40 light years away, hosts rocky, Earth-sized planets, several of which are in the habitable zone.

Since then, astronomers have been using various telescopes to study the planets further and search for signs of life. In this process, they often need to filter out “noise” in their images—such as gas, dust, and planetary objects—sometimes overlooking passing asteroids.

de Wit says, “For most astronomers, asteroids are sort of seen as the vermin of the sky, in the sense that they just cross your field of view and affect your data.”

De Wit and Burdanov realized that the same data used to search for exoplanets could be repurposed to identify asteroids in our own solar system. They applied a technique called “shift and stack,” developed in the 1990s, where multiple images of the same field are shifted and stacked to highlight faint objects by reducing background noise.

This method would require significant computational power to search for asteroids, as it involves testing many possible asteroid positions and shifting thousands of images to match predicted locations.

A few years ago, Burdanov, de Wit, and MIT student Samantha Hassler discovered they could use advanced GPUs (graphics processing units) to handle this massive data processing efficiently, enabling the search for asteroids at high speeds.

De Wit and Burdanov first tested their approach using data from the SPECULOOS (Search for habitable Planets EClipsing ULtra-cOOl Stars) survey, which captures multiple images of stars over time. They also applied the method to data from a telescope in Antarctica. Both efforts demonstrated that their technique could successfully identify many new asteroids in the main asteroid belt.

In their latest study, the researchers used data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which is more sensitive to infrared light. Since asteroids in the main belt are brighter in infrared, JWST’s capabilities made it easier to detect them.

The team applied their method to over 10,000 images of TRAPPIST-1, which were initially taken to study planetary atmospheres. After processing the images, they identified eight known asteroids and discovered 138 new ones, the smallest main belt asteroids detected.

Some of these may be on their way to becoming near-Earth objects, and one is likely a Trojan asteroid trailing Jupiter.

“We thought we would just detect a few new objects, but we detected so many more than expected, especially small ones,” de Wit says. “It is a sign that we are probing a new population regime, where many more small objects are formed through cascades of collisions that are very efficient at breaking down asteroids below roughly 100 meters.”

“This is a totally new, unexplored space we are entering, thanks to modern technologies,” Burdanov says. “It’s a good example of what we can do as a field when we look at the data differently. Sometimes, there’s a big payoff, and this is one of them.”

Journal Reference:

- Burdanov, A.Y., de Wit, J., Brož, M. et al. JWST sighting of decameter main-belt asteroids and view on meteorite sources. Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-08480-z

Leave a Reply