December 3, 2024 by Anna Ettlin, Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology

Collected at: https://phys.org/news/2024-12-infrared-detectors-quantum-dots-keener.html

What do motion detectors, self-driving cars, chemical analyzers and satellites have in common? They all contain detectors for infrared (IR) light. At their core and besides readout electronics, such detectors usually consist of a crystalline semiconductor material.

Such materials are challenging to manufacture: They often require extreme conditions, such as a very high temperature, and a lot of energy. Empa researchers are convinced that there is an easier way. A team led by Ivan Shorubalko from the Transport at the Nanoscale Interfaces laboratory is working on miniaturized IR detectors made of colloidal quantum dots.

The words “quantum dots” do not sound like an easy concept to most people. Shorubalko explains, “The properties of a material depend not only on its chemical composition, but also on its dimensions.” If you produce tiny particles of a certain material, they may have different properties than larger pieces of the very same material. This is due to quantum effects, hence the name “quantum dots.”

For the discovery and synthesis of these fascinating tiny particles, Moungi Bawendi, Louis E. Brus and Alexey Ekimov were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2023. But while the science behind quantum dots is complex, the simplicity instead lies in their processing. Colloidal quantum dots come in a solution and can be applied to different materials by means of spin coating or printing—cheaper, more energy-efficient and more flexible than conventional semiconductors.

From material to process to application

Quantum dots already have a history at Empa. Maksym Kovalenko’s research group in the Thin Films and Photovoltaics laboratory has been working on the synthesis of quantum dots from various materials for more than 10 years. Shorubalko and his team then integrate the quantum dots to produce functioning electronic components, so-called devices—for instance, IR detectors. Together with other Empa experts, they are also researching processing methods and further applications for the quantum dots and the devices made from them.

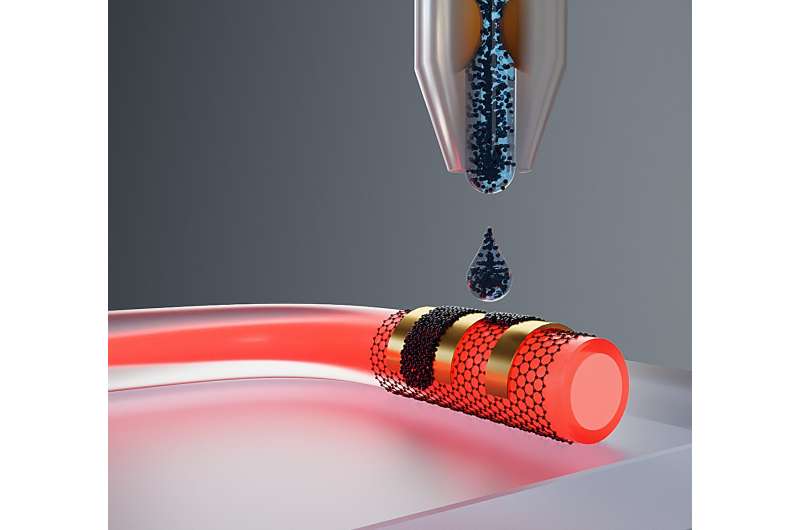

One example: In 2023, Empa researchers succeeded in printing an IR detector made of quantum dots onto an optical polymer fiber—something that is not possible with conventional IR detectors. To achieve this, device specialist Shorubalko and his doctoral student Gökhan Kara worked not only with materials expert Kovalenko, but also with Yaroslav Romanyuk, an expert in printing from Empa’s Thin Films and Photovoltaics laboratory, and with fiber specialist René Rossi from the Biomimetic Membranes and Textiles laboratory. The researchers published their findings in the journal Advanced Materials Technologies in 2023.

One possible application of this technology would be smart textiles. “The global textile market is bigger and faster-growing than the consumer electronics market,” says Shorubalko. Specialized textiles in particular could benefit from the flexible IR detectors, for example functional clothing for firefighters or medical textiles for patient monitoring.

However, Shorubalko also sees great potential in fashion. “If detectors and other electronic components are small, inexpensive and easy to manufacture, we can use them to functionalize our everyday clothing. Current technologies are simply not compatible with textiles.”

Since each detector consists of numerous quantum dots only five nanometers in size, it is possible to manufacture very small IR detectors. In a recent publication in the journal ACS Photonics, Shorubalko, Kara and their peers at Empa and ETH Zurich describe a detector that is smaller than the wavelength of the light it measures. This enables the researchers to record additional properties of infrared light, such as phase or interference, which makes the detector even more versatile.

Unmatched speed

Next, Shorubalko aims to improve the speed of the detector. Fast IR detectors are needed, for example, for lidar, the light-based distance detection technology that helps self-driving cars to find their way, among other things. “Today, lidars use silicon-based infrared detectors, which measure IR light with a wavelength of around 905 nanometers,” says the researcher.

The problem: Although this wavelength is invisible to the human eye, it is still harmful at high power. For this reason, the lidar’s laser can only emit weak light, which limits the range of the entire system, however. Detectors for longer, safer wavelengths do exist, but they are too expensive to be used on a large scale. A fast detector based on quantum dots could provide an alternative and enable powerful, safe and cost-effective lidar systems.

So when will quantum dot-based IR detectors come onto the market? Unlike most novel technologies and materials, patience is not required in this case. “Quantum dot IR detectors are already available on the market,” says Shorubalko. “I’ve never seen a technology make the leap from the lab to the market so quickly.”

Nevertheless, the researchers’ work is far from over. Their task now is to make this promising technology even faster, cost-effective, more flexible and more sustainable.

More information: Gökhan Kara et al, Scaling of Hybrid QDs-Graphene Photodetectors to Subwavelength Dimensions, ACS Photonics (2024). DOI: 10.1021/acsphotonics.3c01759

Journal information: ACS Photonics , Advanced Materials Technologies

Leave a Reply